Trauma during development or, childhood trauma, changes physical brain architecture and ability to learn and social behavior. It impacts two out of three children at some level, but I didn’t even know what it was…

Childhood trauma, or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can be defined as a response of overwhelming, helpless fear to a painful or shocking event.

ACEs include physical, emotional and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, a missing parent (due to separation, divorce, incarceration, death), witnessing household substance abuse, violence, or mental illness and more.

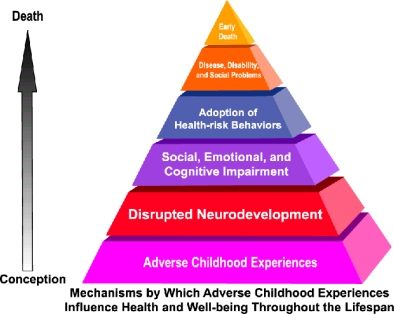

The children are not sick or “bad”. Childhood trauma is an injury. It happens TO the child. In turn, when they become adults, many re-enact their unaddressed trauma, injuring the next generation in a merciless cycle of pain and fear. When the injuries fester unaddressed, they set off a chain of events leading ultimately to early death, according to the CDC.

Developmental trauma changes the architecture of a developing child’s physical brain.

Part 1: The changes to the physical structure of the brain impair academic efforts. They damage children’s memory systems, their ability to think, to organize multiple priorities (“executive function”), and hence to learn, particularly literacy skills

Part 2: The changes to the neurobiology predispose hypervigilance, leading trauma-impacted children to often misread social cues. Their fears and distorted perceptions generate surprising aggressive, defensive behaviors. The ‘hair trigger’ defenses are often set off by deep memories outside of explicit consciousness.

Adults’ view, from the ‘outside’, of the seemingly illogical, or worse, oppositional behavior, is one of shock, confusion, frustration and maybe anger.

If we act on our uninformed views, we risk re-triggering more of the child’s trauma, and even more aggression. I confess, as a less experienced classroom teacher, I often did exactly that.

Outward behaviors are easy to recount.

The inner pain and fear are often intentionally camouflaged and nearly impossible to perceive from the outside.

The trauma history which is connecting the inside fear to the outside behavior is often buried so deeply that even the injured can be unconscious of the connection.

ACE-impacted kids are more common than seasonal allergy sufferers

Childhood trauma is not a “color” issue. It’s not a geography issue. It’s not an income issue. Experts including Surgeon Generals and the U.S. Attorney General have used the specific terms "national crisis’", and "epidemic". The CDC says trauma impacts are critical to understand..

CDC scientists found that even in beautiful, suburban San Diego about one-fourth of middle class, mostly white, college educated, working folks with medical insurance had THREE or more ACEs!

Three or more ACEs is significant because 3+ ACEs correlate, over a lifetime, with doubled risk of depression, adolescent pregnancy, lung disease, and liver disease. It triples the risk of alcoholism and STDs. There is a 5X increase in attempted suicide.

Children can not address their trauma alone. They need our help.

Nevertheless, presently many adults ignore childhood trauma. It’s rarely spoken about.

Other adults normalize the pain and fear of the injured child, thinking: “They’ll get over it.” It’s actually the opposite. Young children have fewer coping mechanisms and their immature brains are still developing. The impacts of trauma are actually greater on the still-developing brain.

Schools are not trauma-informed organizations

I am embarrassed to admit my own ignorance.

I did know about the inner pain and fear of my students more intimately than most. I began, and still begin, every school year by visiting my families, sitting in their living rooms to discuss school, life and their concerns about their child. In the classroom, I quickly experience the child’s outward behaviors which could seem random, nonsensical, and often angry.

Yet, I still did not easily connect the outward behavior in class to the fear or pain.

As an adult, the classroom seems “safe.” There isn’t an obvious or logical connection to continuing fears, in our safe context. It seems contradictory.

What I forget is that the pain and fear are not in the environment.

The pain and fear are hidden inside the child: They bring intense fear memories with them like they bring their backpack (wherever they go).

Making the connection, intellectually, was made even more difficult in the moment, in the midst of emotional, intentionally distracting, sometimes screamed, personal insults or abusive attacks from the triggered child.

Even when I was able to stay calm myself, and then connect the (seeming) anger to the (hidden) fear, that was only the beginning. I still did not understand.

There’s more.

The group context, or the social complexity may be the most difficult aspect of all.

If I did maintain composure, then I realized quickly that the other 30 children in the room did not all wait calmly or politely for me so I could focus solely on de-escalating one of their peers.

I also learned the hard way that when I maintained composure in the midst of the barrage, it seemed like “unfair” leniency to other children. They see only the aggressive outward behavior and they expect “punishment”.

Even more learning: the aggression of one student and the related commotion will likely trigger a second student’s fear, and maybe others, too.

Keeping the academic context in mind: All of the above is about one instance only. Meanwhile, each minute lost to deescalating that single student is a minute lost to academic endeavors for all 30.

It’s complex.

Now, imagine NOT being trauma-informed and facing 20 to 30 students, and NOT knowing that 25% to 50% are impacted by trauma.

Success would require becoming expert at detecting multiple, virtually undetectable triggers, within multiple students. It is not quick or simple or instinctive.

There’s more.

That same teacher must become expert at defusing all those students’ fear triggers, and all in advance of any “fight or flight” response.

All day today.

All week this week.

All month this month.

More context: A teacher is not permitted to consider adjusting the scope or pace of the Common Core, or academic, national standards that are linked lesson-by-lesson and which lead to standardized testing. These regular, test stresses are controversial for many reasons. Trauma adds more controversy. First, the stress can re-trigger traumas. Second, the higher concentration of violence and stress in urban settings, with higher concentrations of students of color, and higher concentrations of trauma impairing cognition keeps the achievement gap alive and well.

Let’s pile on top: Budget cuts for public schools each year translate to fewer adults with fewer resources to accomplish trauma-informed education, year after year.

Teaching in this context becomes nearly impossible at many points.

We are trying to scoop water out of a boat with gaping trauma-holes in the bottom.

Trauma-impacted children are losing their right to equally access their education, while adults stand by, while school districts stand by, while states stand by.

That leads, of course, back to the central aspect of the context:

Schools are not trauma-informed organizations

Just as children can not address their own trauma alone, teachers can not create trauma-informed school organizations all alone.

“Success” with trauma-impacted students comes slowly, over time. It is crucial to maintain a predictable, calm, safe environment, and safe relationships, school-wide, with all adults responding calmly, hour by hour, day by day, month after month. And that’s only the beginning.

Training and support are essential: classroom and personal training and support for school-wide staff, on-going. Teaching trauma-impacted children is an intense role.

Training needs to include the impacts of developmental trauma and then also strategies to avoid our school systems themselves adding more trauma. We need to become experts in avoiding escalation and in de-escalating trauma-impacted children, not re-triggering or re-traumatizing them. Otherwise, our attempts at “academics” will be, at best, inefficient, more likely futile.

Simultaneously, at the school level, we need to identify, or in some way, screen for students’ trauma histories. It’s too easy to miss camouflaged trauma, in particular those who are quietly dissociating.

‘Trauma-informed’ includes physical space for students’ off-line de-escalation, away from the ‘crowd’, noise, stress, and triggers — not simply ‘the corner’ of the same classroom with 30-plus other folks trying to learn.

‘Trauma-informed’ includes an adequate ratio of adults to students in a classroom. One adult for thirty children, of which, the data says, six-to-eight children (minimally) are trauma-impacted, is inadequate, unethical, and directly in conflict with ‘equal access’ to education for all the children in the same classroom.

‘Trauma-informed’ radically restructures discipline away from ‘zero-tolerance’. Otherwise, school systems continue filling the “school-to-prison pipeline” with injured, trauma-impacted children.

Further, we need to confront the impotence, the stress, the damage from the academic paradigm of synchronized timing and “standardized” testing model.

Finally, we should be adjusting efforts against “achievement gaps” to a laser focus on communities with greater violence, stress and trauma.

In spite of the devastating impacts and implications, Developmental Trauma remains “the elephant in the [class]room”! That is wrong, morally wrong.

.

Help build awareness of developmental trauma

“Nowhere to Hide” blogposts are designed to help grow awareness of childhood trauma. They each focus on a single component of the workings of developmental trauma, via a real life example in short, “30 second” or “60 second” soundbite Links, akin to “Public Service Announcements” (PSAs).

All the narratives are all about real kids (with pseudonyms). I live in community with them, and know them personally as students, neighbors and friends. These are not “combined” or imaginary narratives, or caricatures.

Most of the children in the stories lived in a single neighborhood. Each one passed through my classroom. More than half were in the same classroom, the very same year”! Difficult to imagine…

Trigger warning: the children’s experiences in the vignettes are unvarnished. Their responses to their trauma may trigger painful memories.

Please, share the “PSAs” widely.

The “Nowhere to Hide” PSA Links are meant to be easily, widely shared, one or two at a time, in social media. Share one today!

Nowhere to Hide: Maria; Fight, flight or freeze

Nowhere to Hide: Andre’s Fear; What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

Nowhere to Hide: Jamar’s Hyperarousal

Nowhere to Hide: Roberto’s Dissociation

Nowhere to Hide: Danny’s Memory

Nowhere to Hide: Ashley’s “Normal” Education? Part 1

Nowhere to Hide: Ashley’s “Normal” Education? Part 2

More to come

A different, original series, “Peek Inside a Classroom”, provides much more detailed looks inside my classroom, primarily focused on specific students: Jasmine, Danny and Jose. Other vignettes are captured in broader looks at education reform concepts: “Failing Schools or Failing Paradigm?” and “Effective Education Reform.”

Peek Inside a Classroom: Jasmine

Peek Inside a Classroom: Danny

Peek Inside a Classroom: Failing Schools or Failing Paradigm?

Peek Inside a Classroom: Effective Education Reform (with Dr. Sandra Bloom, M.D.)

“Like” us at “Trauma-Informed Schools” on Facebook

Comments (0)