Costco is out of toilet paper and CVS is out of cough syrup. Your group fitness class and your favorite restaurant are closed. Your cousin keeps posting memes on instagram about some conspiracy theory and your co-worker brags on about how she hasn’t been sick in years so she’s not worried about germs. This is not a nightmare. This is real life in 2020 thanks to COVID-19, aka the coronavirus.

On March 11th, three months from when the first cases of pneumonia were reported in China, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. With a composed and articulate delivery, WHO chief Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus expressed that this declaration could lead to a response of “unjustified acceptance that the fight is over” or “unreasonable fear.” He wasn’t wrong. With what seemed like an air of hope, he also reported that this declaration should not change the approach governments are taking to stop the spread, or flatten the curve. Fear is quite the motivator. As we introduce in The Basics, fear can activate our stress response system (aka our survival brain) and when that happens, reason and logic can go out the window. We have a reaction to a real or perceived threat to safety that affects our body, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. In this scenario, COVID-19 is the trigger that activates unique fears and responses in each person. For some, the response might be fight or flight. For others, it might be freeze or fawn. Some people get angry and might fixate on finding someone to blame, other people might feel overwhelmed and shut down completely or go on with life as usual, Still others feel guilty that people are suffering and turn to people-pleasing or caregiving. We adapt.

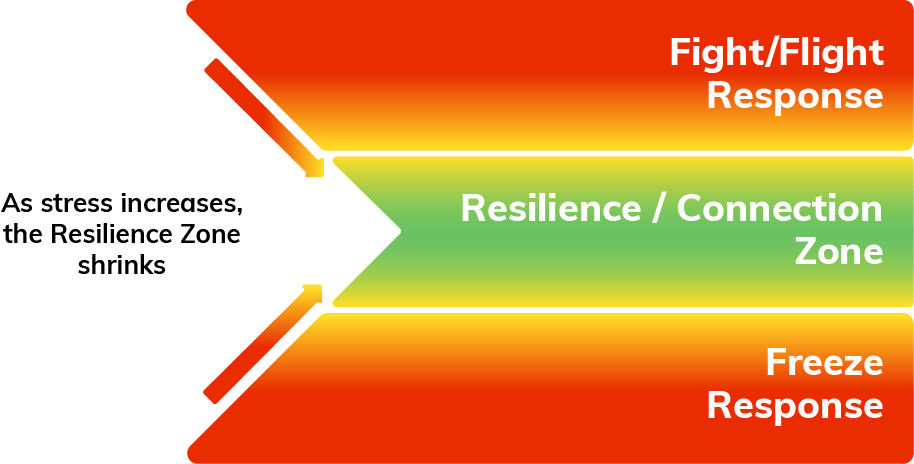

Fear is quite the motivator. As we introduce in The Basics, fear can activate our stress response system (aka our survival brain) and when that happens, reason and logic can go out the window. We have a reaction to a real or perceived threat to safety that affects our body, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. In this scenario, COVID-19 is the trigger that activates unique fears and responses in each person. For some, the response might be fight or flight. For others, it might be freeze or fawn. Some people get angry and might fixate on finding someone to blame, other people might feel overwhelmed and shut down completely or go on with life as usual, Still others feel guilty that people are suffering and turn to people-pleasing or caregiving. We adapt.

You may be wondering, “so what am I supposed to do about it?”

First, we can take a trauma-informed approach when responding to one another during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) uses the 4 R’s: realizing that each person’s history of trauma can affect them today; recognizing the ways people are thinking, feeling, acting as a normal response to an abnormal situation; responding with compassion and understanding (while still holding them accountable and practicing healthy boundaries for yourself); and reducing re-traumatization. The key principles of a trauma-informed approach include safety at the forefront.

Second, we can all practice getting and staying in our resilience zone. When we read news headlines or talk to a co-worker that seems to be communicating with exclamation points, it can be contagious. If we’ve had a life full of stress, trauma, and adversity, it can become even more difficult to distinguish between what is “reasonable” and “unreasonable.” Some of us may have a hard time putting our thinking cap on when emotion is in the driver’s seat. During times of high stress, feeling angry, guilty, and overwhelmed makes perfect sense given the person’s life experience. But staying staying there or allowing those emotions to inform our behaviors can impact our health.

Strengthening our “resilience muscle” starts with awareness. What am I noticing in my body, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors? Am I inside or outside of my resilience zone? When I read a headline or hear some news and the words are upsetting, what is my reaction? Do I stockpile toilet paper or do I think about ways I can continue to connect with others or support those who are more vulnerable during a time when physical distancing is a necessary intervention? That balance will be the difference between succumbing to the frenzy and chaos and moving through this pandemic with resilience.

To learn more about what your baseline in the window of tolerance might be…

GET YOUR ACE SCORE HERE or TAKE A RESILIENCE INVENTORY HERE

Image credit: TW @SIOUXSTEW based on Thomas Splettstöber TW: @SPLETTE and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Comments (1)