At Teralta Park, Arturo Soriano (l) with his wife, Gabby, holding baby Joshua, and their kids Daniella (between them) and Adrian (kneeling), spend time with Kenneth (arms folded), Claudia Ruiz and her mother, Michelle Massett. Behind them, Coach, wearing red gloves, comes to the park to spar with the youth.

_________________________________

It’s a warm spring afternoon and Arturo Soriano is in his old stomping grounds—at Teralta Park, a small urban park atop a sunken freeway in San Diego’s City Heights neighborhood. As a teenage gang member in the 1980s, Soriano roamed the park and the surrounding streets before spending the better part of two decades in prison. Now 40, he has returned with a different mission.

Since 2014, Soriano, his wife Gabby, and more than a dozen other volunteers have been coming to the park to shoot hoops, barbecue and build connections with the young people of City Heights, a neighborhood where poverty, trauma and violence have intersected for decades, passing from one generation to the next. They are also running workshops on youth leadership and restorative justice at a neighborhood church. They call their fledgling, unfunded group Youth Empowerment.

“We have 15, 16 community mentors, all former gang members, giving back, doing good,” Soriano says. “We’re all working to get these kids on the right track.”

A few blocks away, mothers of children at Cherokee Point Elementary School, the first school in San Diego to become trauma-informed, are gathered in a classroom dedicated to their use. The women, mostly immigrants from Mexico, have been receiving leadership training and learning about the impact that trauma and punitive parenting practices can have on children and families. They’re also learning techniques that promote healing. Having experienced domestic violence or abuse themselves, they are determined not to do to their children what was done to them.

Cherokee Point Elementary mothers, (l to r): Anabel Barajas, Evelin Molina, Nancy Serna, Maria Gonzalez, Carmen Rodriguez

"Most parents are not informed,” says Nancy Serna, a mother of four whose 9-year-old son attends the school, as did two of her older children. “It’s important that they know about the effects trauma can cause in their children and in themselves. If they know about it, what it costs, no parent will want their children to go through that.”

Soriano and Serna represent the grassroots side of an impressively coordinated movement that has been taking shape in all corners of this sprawling city and county, the nation’s fifth most populous. It’s a movement with the wonkiest of names — ACEs movement, sometimes trauma-informed or resilience-building movement — and the most ambitious of goals.

The county Board of Supervisors and the San Diego City Council have committed to making social service, criminal justice, child welfare and other agencies “trauma-informed.” What that means in English is that the county wants to change the way it provides services to children and families by being more compassionate, less punitive and more welcoming in order to keep the traumas of one generation from being transmitted to the next, and, in the process, solve some of the community's most intractable problems.

The approach is seeing some impressive results. For example, from the 2011-2012 school year to the 2014-2015 school year, the school district, which serves 129,000 children, reduced overall suspensions by 38 percent and expulsions by 60 percent. (Cherokee Point no longer expels or suspends students.) The Homeless/Transition Age Services at San Diego Youth Services has seen a drop in incidents that involve physical violence or require police intervention. And during the first year of operation of a new trauma-responsive juvenile detention facility, the 223 kids who lived there engaged in no violent incidents — a remarkable situation for such facilities — and most experienced declines in the trauma-related symptoms they had been experiencing, according to an internal evaluation.

County agencies, nonprofits and schools have been training staff members to understand how adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, can affect children and how to recognize and help a child or parent who has been affected by these experiences. The best of the trainings – though not all of them – review the vast body of science that has emerged in recent years that demonstrates the powerful, lifelong role that adversity and trauma have on the developing brain of a child and their physical and emotional wellbeing.

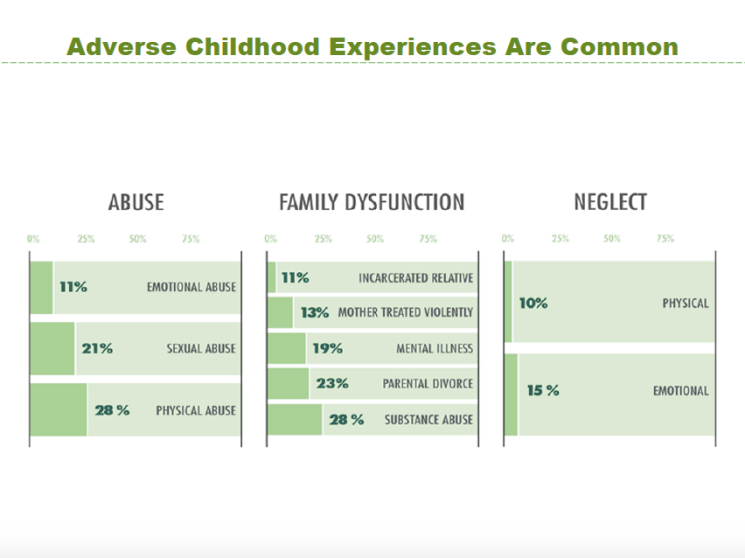

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) looked at 10 types of childhood trauma: physical, emotional and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; living with a family member who’s addicted to alcohol or other substances or who’s depressed or has other mental illnesses; experiencing parental divorce or separation; having a family member who’s incarcerated, and witnessing a mother being abused. Other subsequent ACE surveys include racism, witnessing violence outside the home, bullying, losing a parent to deportation, living in an unsafe neighborhood, and involvement with the foster care system. Other types of childhood adversity can also include being homeless, living in a war zone, being an immigrant, moving many times, witnessing a sibling being abused, witnessing a father or other caregiver being abused, involvement with the criminal justice system, attending a zero-tolerance school, etc.

The ACE Study found that the higher someone’s ACE score – the more types of childhood adversity a person experienced – the higher their risk of chronic disease, mental illness, violence, being a victim of violence and a bunch of other consequences. The study found that most people (64%) have an ACE score of one; 12% of the population has an ACE score of 4. Having an ACE score of 4 nearly doubles the risk of heart disease and cancer. It increases the likelihood of becoming an alcoholic by 700 percent and the risk of attempted suicide by 1200 percent. (For more information, go to ACEs Science 101. To calculate your ACE and resilience scores, go to: Got Your ACE Score?)

The ACE Study also found that it didn’t matter what the types of ACEs were. An ACE score of 4 that included divorce, physical abuse, an incarcerated family member and a depressed family member had the same statistical health consequences as an ACE score of 4 that included living with an alcoholic, verbal abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect.

The ACE Study is one of five parts of ACEs science, which also includes how toxic stress from ACEs damage children's developing brains; how toxic stress from ACEs cause chronic diseases; and how it can affect our genes and be passed from one generation to another (epigenetics); and resilience research, which shows the brain is plastic and the body wants to heal. Resilience research focuses on what happens when organizations and systems integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices, for example in education and in the family court system.

In San Deigo, representatives of schools, youth-service agencies and even probation and police departments meet regularly to share information and insights in an effort to coordinate and collaborate. The term trauma-informed has become so common it has morphed into a noun—as in “we’re doing a training on trauma-informed”—and TI has become a common acronym.

But four years after the county board made implementing a trauma-informed approach part of its Live Well San Diego initiative—a set of goals for improving health and safety in San Diego—progress has stalled in some areas and flourished in others.

For almost a decade, one group of people, working largely as volunteers, led the effort to get San Diego to do a better job of understanding and addressing the impact of trauma on children and families. From its birth in 2008, the San Diego Trauma-Informed Guide Team grew from six founders to a coalition of more than 160 people working in human service agencies across the county.

The Guide Team functioned as a grassroots network, convening to share ideas and organizing training sessions on trauma-informed practice for dozens of agencies and hundreds of staff and community members. Guide team members were encouraged by their agencies to spend an hour here or there doing work to build the network. A Facebook page was created that posted articles and listed events.

In 2015, a coalition of San Diego groups that including the Guide Team was awarded a two-year grant called Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities, or MARC, to expand the countywide effort to respond to ACEs. Since then, the coalition’s work, administered by the community services organization Harmonium, has been focused primarily on developing a strategic plan, and as a result the Guide Team has largely stopped doing training. The MARC program nationally is managed by the Health Federation of Philadelphia and funded by The California Endowment and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The Guide Team and other members of the coalition are exploring some difficult issues, says Pam Hansen, a senior director at the San Diego Center for Children and the Guide Team co-chair. One is how to increase the voice and participation of community members in a way that doesn’t treat them as tokens and provides them with real benefits. Still, the hiatus in training has disappointed many people.

A change in focus is part of the process of change, especially one as monumental as changing organizational cultures and practices, says a consultant who has been working with San Diego County on the systems-change effort, which has also slowed. Stop-and-go progress is only natural when large, complex organizations try to create major systems change.

“It has stalled in a couple of places and run into some roadblocks and friction,” said the consultant, who asked not to be named. “Some people want it to go quicker than it has gone. But this is a process and everyone operates at different speeds. When there’s an incredible amount of tension and friction—that’s often when the breakthrough happens.”

One organization making steady progress is a youth group called Youth Voice. For the past couple of years, Arturo Soriano’s stepson, 16-year-old Adrian Mejia, has been going every Thursday afternoon to Mid City Police Station, less than a mile from Teralta Park. There, in a meeting room upstairs from the station and its holding cells, Mejia participates in Youth Voice. Soriano often attends as well. How the two of them came to be there is a story in itself.

One Thursday morning two years ago, when he was a sophomore, Adrian was ambushed sitting in front of Arroyo Paseo High School and beaten so badly he passed out. In those days, he says, “I was using (drugs) and I hung out with homies,” though he wasn’t himself a gang member, he says. A teacher and friends found him unconscious on the sidewalk and he was taken to a hospital.

Police officers visited him at the hospital and he declined to press charges. But one of the officers working in juvenile services, John Cooksey, had a proposition: Adrian should come that afternoon to the regular meeting of Youth Voice at the police station.

“I was sketchy about it, but he mentioned some names of friends,” Adrian says. “I figured if they can go, I can go. I got out of the hospital in the afternoon and went straight to the program, banged up and bruised with ice packs on my face.”

Soriano was at the hospital when Officer Cooksey made his pitch to Adrian, and then invited Soriano to come along as well. “I saw his passion and his genuineness,” Soriano says.

So Arturo and Gabby went with Adrian to the Mid-City station—the first time, Soriano says, that he entered a law enforcement facility without being in handcuffs.

At Mid City Police Station, San Diego Police Dept. Capt. Michael Hastings (in uniform), others hear Youth Voice members present about ACEs science.

“Uncomfortable and out of place, nervous system out of whack,” Soriano recalls feeling.

Adrian has been going to the meetings ever since. “I never miss a Thursday at Youth Voice,” he says. “It’s like my second family.”

At their first meeting, Soriano also met Dana Brown, a member of the city’s Commission on Gang Prevention and Intervention and a self-described social entrepreneur who’s been active in building San Diego’s effort to address trauma. (She has since become the Southern California community facilitator for ACEs Connection, the social networking and community support arm of ACEs Connection Network, of which ACEs Too High is part.) Brown recruited Soriano to the cause and helped him launch his Youth Empowerment effort.

Last spring, at a Youth Voice meeting at the station, Adrian and four young women practiced a presentation on ACEs science and trauma-informed practices they’d recently given to a counseling class at San Diego State University. Their audience included Captain Michael Hastings, chief of the Mid City Division. He was seated next to two former gang members, Francisco Mendoza, a training specialist for the prison reentry program Second Chance, and Louis Vargas.

Youth Voice leaders do presentation about ACEs science: (left to right) Adrian Mejia, Katherine Rodriguez, Tatiana Sanchez, Jessica Rivera, Sienna Gomez.

“We’re here to talk about trauma,” begins Sienna Gomez, 18. “Trauma isn’t just one thing; there are different types.” She explains some of the distinctions between experiencing a single traumatic event and regularly experiencing chronic trauma. “Now I’m going to present a 911 phone call.”

Next, we hear the voice of a 6-year-old-girl named Lisa talking to a 911 dispatcher, sobbing and begging for help as other children scream in the background. Gomez explains that Lisa is watching her mother assaulted by her boyfriend.

“When I first listened to his, I thought I was back in my own home. I was shaking, I was crying. It made me angry,” Gomez says. “Listening to this little girl, I remember how I was alone and I wish I would have felt someone else was there for me. Now, being involved in Youth Voice, I realize I am not alone. There are people here to help me.”

As the presentation continues, Adrian Mejia shows a video clip about the effects of incarceration on children, then adds a personal note. “My Dad has been incarcerated all my life,” he says. “I’ve only seen him five times. The last time, I was 6. I remember I threw my hands up on the glass window wanting to reach out to him.”

While he talks about the pain of being separated in this way from his father, what he doesn’t say is that having an incarcerated family member is considered an adverse childhood experience—much like being abused, neglected, or having a parent with substance abuse issues. All of these dramatically increase the risk of a child developing serious physical or mental health problems during their lifetime.

While activists like Soriano are reaching out to young people and families at the grassroots level, some county agencies and community-based nonprofits are working to educate their own staff members about the impact of trauma and to change the way they receive and serve clients.

“We want our buildings to be inviting and welcoming places,” says Dale Fleming, director of strategy for San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services. As an example, in 2015, the department opened a new Live Well Center — the kinder, friendlier term the county uses for its multi-service centers. Built on the site of an old supermarket in Escondido, it has been remodeled with high ceilings and natural light to help visitors feel comfortable when they come to apply for food stamps, connect with a nonprofit group, or get help from a veteran’s organization.

“San Diego embraced trauma-informed care very early on, because it has always been one of those places that valued collaboration,” says Stephen Carroll, division director for Homeless/Transition Age Services at San Diego Youth Services. The agency, which provides housing and counseling support to youth, has revised a punitive, rules-based approach that was too often driven by inflexible program models and not by the needs of the youth, Carroll says.

“We had created what we thought were ideal structures, rules and regulations and assumed this was so good that any youth would do well here regardless of circumstance or background,” he says. The program had taken a value—the belief that the best way for young men and women to better their lives was to finish school—and turned it into a bottom-line demand.

“If kids didn’t go to school, they couldn’t come to shelter,” Carroll says. “But boiling it down to a rule didn’t take into account individual circumstances—that many students struggled with mental health issues, were being bullied, or had been out of school for a while. They weren’t used to the structure and maybe school wasn’t their top priority like being in a safe shelter.”

Carroll asked his team some rhetorical questions: “If we think we have the best program and we tell youth to leave because they’re not following the rules, what are they taking from that? If a youth acts out their anger and we kick them out, what are we teaching them? They leave without any more tools in their toolbox.”

So, the agency shifted gears. It began offering a broader array of services including yoga, mental health counseling and self-care groups. It created a youth advisory council to obtain input from its young clients as it revises its policies. And it changed the way it evaluates client progress: Now, instead of looking at old benchmarks—whether a young person goes to school, earns money or pays rent—staffers ask young clients to describe their own needs.

“There’s a lot more focus on personal wellbeing in addition to productivity,” Carroll says.

Carroll also increased the focus on personal safety to prevent clients from harming themselves or others. Staff members work with each youth to create an individualized safety plan, asking each young person a series of questions: What are the early warning signs that you really need help, and soon? What are some ways you can help yourself? How can others help you, and who are the people you would most trust to assist you in a time of need?

Shifting from “rules and protocols on everything” to those based on safety has led to a drop in incidents that involve physical violence or require police intervention, Carroll says. At the same time, the agency has also focused on self-care for its 200 staff members by setting up walking, running and knitting groups and expanded health and wellness programming. Staff and volunteers also attend sessions to help them manage the stress of working with traumatized youth.

Helping staff members take better care of themselves may have contributed to an unexpected benefit: Health insurance premiums paid by the agency for its staff declined by around 5 percent. Human Resources Director Fei Li Tan Twite thinks that may stem from staffers having fewer doctor’s visits as they cut their stress and improved their self-care.

If any agency needs to address trauma among clients, it would be the juvenile probation department, which manages young offenders in detention facilities and supervises them when they’re on parole. San Diego’s new chief probation officer, Adolfo Gonzales, was hired one year ago and says he is working to change the atmosphere of the detention facilities to make them “more therapeutic and rehabilitative.”

Gonzales inherited a department under fire by rights advocates for excessive use of physical force and pepper spray, and an atmosphere that exacerbated, rather than eased, the stress levels of young people with significant histories of trauma and adverse experiences.

In 2013, there were 24 suicide attempts among the young detainees, up from 10 the previous year. One of those attempts succeeded. In September 2016, Rosemary Summers, a 16-year-old girl with a history of sexual exploitation, depression, and suicidal thoughts, hung herself inside her cell after covering the windows with paper. The county later agreed to pay $1 million in a legal settlement with her family.

A February 2016 report from Disability Rights California, a legal rights organization, reported that extensive use of pepper spray by staff members had helped create an “atmosphere of violence and intimidation in the facility.” Last year, the San Diego Union Tribune reported that pepper spray was used 249 times in 2015, up from 208 times the year before.

Scott Huizar, the department’s deputy chief for institutional services, said that pepper spray use declined greatly over the past five years, outpacing the decline in the number of incarcerated youth. From 2011 to 2016, the detained population went from 759 to 385, a 49 percent decline, while the number of pepper spray incidents fell 67 percent, he said.

Gonzales was named chief probation officer in March 2016. A 26-year veteran of the San Diego Police Department and former police chief for National City, he says he understands the young people in his charge because he was raised “in the barrios of South San Diego” and saw family violence first-hand. “I grew up in that environment and that’s what motivated me to be a cop – to change things,” he says.

That same month, after eight months of planning, the department opened a 20-bed “Trauma Responsive Unit” for young males at the Kearney Mesa Juvenile Detention facility. The unit, called the TRU, was designed to be homier and less institutional as a way to help the young men stay calm, Gonzales says.

“We painted a sky with clouds on the ceiling, brought in brighter furniture and created smaller classrooms,” he says. Bedrooms have walls with chalkboard paint, allowing youth to draw, make lists or write inspirational quotes.

Geoff Twitchell, the department’s director of treatment and clinical services, developed a four-hour training program for the staff that explored the neurobiology of trauma and its role in child development, and offered techniques for interacting with youth that are less likely to trigger or re-traumatize them.

The youth are offered similar trainings, provided in four group sessions that teach them how the body reacts to stress, how to recognize when they’re becoming triggered, and ways they can better manage their emotional responses and solve problems. These kinds of coping skills “can help people manage their tendency to be reactive and to actually calm themselves and regulate their emotions,” Twitchell says.

Since many of the youth are released before completing the four sessions, the department is contracting with an outside agency to continue and expand the training in a community setting.

The department just completed an internal evaluation of the unit’s first year, which ended Feb. 28, and claims impressive results. According to the report, 223 young men, with an average age of 16, were placed in the TRU during the year. No violent incidents took place in the unit, while two comparable male units had 29 and 14 violent incidents during the same period. The lack of violence in the TRU “eliminated the need for use of force,” the evaluation found.

Three suicide attempts occurred in the TRU, compared with 15 and 25 in the other units. About half the youth completed all four training sessions, and for them, the evaluation found a 76 percent drop in trauma-related symptoms. But even among those who only took part in one of the training sessions, 61 percent had their trauma symptoms decline. The program cost $180,000, $45,000 for physical modifications of the facility and the rest for training and supervision.

Given the success of the pilot phase of the program, Gonzales says the department is now evaluating rolling it out to its other detention facilities. His goal is to change the culture of the department and to help eliminate the “school-to-prison pipelines” that run through juvenile detention facilities like his. Already, he says, the department is creating “a much different organization, a much different institution, a much different environment for our kids."

Comments (0)