The inputs a brain experiences during its developmental stages have a profound impact on whether that person will develop a substance use disorder (if they choose to drink or use other drugs).

In turn, developing a substance use disorder (SUD) as a tween, teen, or young adult dramatically influences that person's brain development.

And why is understanding this causality important?

The risk factors for developing a substance use disorder are the result of inputs the brain experiences (or inherits) during its developmental stages in utero through early-to-mid twenties. In turn, the stage of brain development and the developmental processes in play when an SUD begins profoundly impacts the brain's development from that stage forward.

When we understand this mutual cause-and-effect relationship between substance use disorder and brain developmental stages, we are better prepared to embrace and use brain- and science-based prevention, intervention and treatment programs and strategies.

Understanding brain developmental stages

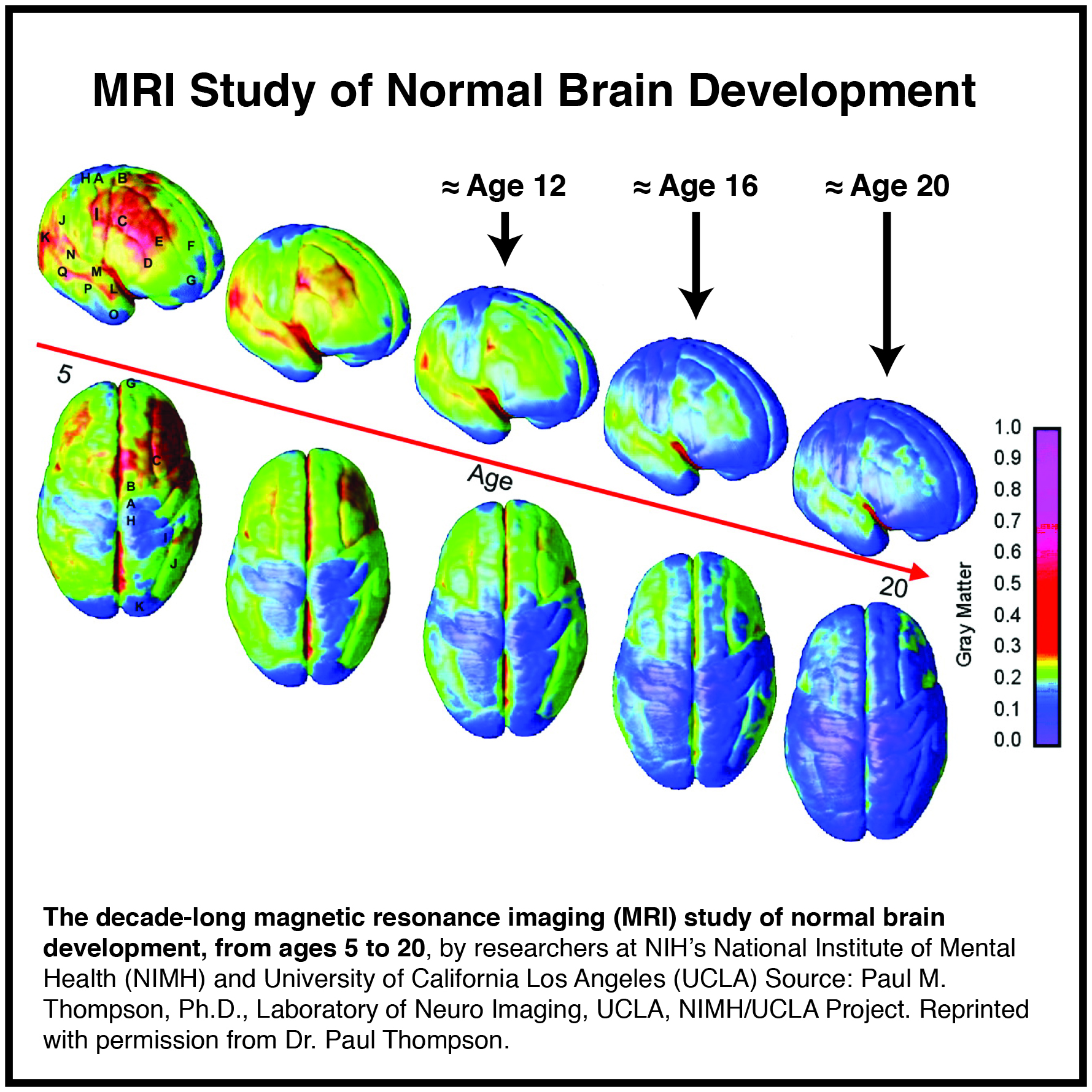

Advances in imaging technologies now allow scientists and medical professionals to observe and study the live, conscious human brain like never before. The resulting findings – some in just the recent 10-15 years – are revolutionizing our understanding of this three-pound organ. Think of it. Just three pounds, just a fraction of our total body weight, and yet it controls everything we think, feel, say, and do.

If our brain doesn’t work, we can’t feel pain or love or run or drive a car. If our brain doesn’t work, our heart can’t pump, our lungs can’t breathe, and our limbs can’t move. If our brain doesn’t work, drinking alcohol or using other drugs would have no effect on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

The following image showing brain development ages 5 - 20 (development that's now understood to continue until age 22 on average for girls/women and 24 for boys/men) gives us a visual of "normal" brain development.

What happens to the brain -- like adverse childhood experiences -- as it's going through key developmental stages has a profound impact on whether that person will develop a substance use disorder (if they choose to drink or use other drugs). And that's because of the risk factors for developing a substance use disorder AND the stage of brain development at the time the substance use/abuse began.

Understanding the risk factors for developing a substance use disorder

One of the key risk factors for developing an SUD is childhood trauma, what we now refer to as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). The other four are social environment, genetics, mental illness, and early use. To explain these, I share the following excerpt from my latest book, 10th Anniversary Edition If You Loved Me, You'd Stop, pages. 88-92:

Genetics. Genetics is responsible for about half the risk for developing an alcohol use disorder.40 It’s not that there is a specific alcoholism gene – at least not one that has been identified, yet. Rather it’s the concept of genetic differences that underpins this risk factor. Just as we inherit certain genetic differences from our parents that determine our eye color, hair color, skin color, and body type, for example, so too are there genetic differences that influence how our brain/body interacts with ethyl alcohol. These differences may include higher or lower levels of dopamine neurotransmitters or higher or lower levels of the enzymes in the liver that break down the ethyl alcohol, as examples. These genetic differences are passed along from one generation to the next. So, looking at your loved one’s family history – mom, dad, grandparents, siblings, aunts/uncles – to see if they had/have alcoholism (or other drug addictions) is one way to determine whether genetics is a risk factor for your loved one.

Mental Illness (also called mental health disorder). Mental illnesses, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar, PTSD, ADHD, are also brain changers / brain differences. In other words, the way the brain cells of a person with a mental illness communicate with one another is different (for a variety of reasons) than the way the brain cells of someone without that illness communicate with one another. This is important to understand because “[t]hirty-seven percent of alcohol abusers and 53 percent of drug abusers also have at least one serious mental illness.”41

Why is this important to know? Because the person may turn to alcohol (or other drugs) to self-medicate the symptoms of their mental disorder – like drinking to relieve anxiety, for example. Drinking alcohol may also worsen the symptoms of their existing mental illness. Either way, their brain creates brain maps that connect the use of alcohol with the symptoms they experience because of their mental disorder.

When a person has both a mental illness and alcoholism, that person has two brain diseases (disorders). This is known as having co-occurring disorders, and both must be treated at the same time, in order for the person to succeed in long-term recovery. [These co-occurring disorders are similar to a person who has both cancer and diabetes. Doctors would not stop treating the diabetes while they treat the cancer, nor would the same treatment work for both diseases.] If not treated at the same time, the absence of the alcohol will likely trigger the brain to drink because that’s what the brain mapped as its soother for the symptoms of the mental disorder.

Not treating co-occurring disorders at the same time is one of the key reasons people relapse (that is, they go back to drinking after they’ve stopped for a period of time).

Early Use. It is crucial to recognize this risk factor because the adolescent brain is not the brain of an adult, as was explained in Chapter 4. For example, the adolescent brain interacts with ethyl alcohol in a different way than does the adult brain for a number of reasons. Additionally, the key brain developmental processes occurring from ages 12 through early 20s makes the tween/teen/young adult’s brain especially vulnerable to mapping an alcohol use disorder (or another drug use disorder).

For example, as you read in the last chapter, telling adolescents in the 12-15 age range to “just say, ‘No'” doesn’t typically work. This is because the onset of puberty is “telling” the adolescent brain to “take risks” and “turn to your peers.” If their peers are saying, “yes” to risks, drugs and/or alcohol, it’s likely that the adolescent will, too. This action does not mean they are bad kids. It simply means their brain’s instinctual wiring – the wiring that activates during puberty – is in charge.

Additionally, early use – early abuse – of alcohol wires in brain maps around the finding, seeking, using, hiding, covering up, and getting over the effects of drinking at an especially vulnerable time. This vulnerability is the result of the brain’s pruning and strengthening processes. Not only that, but early abuse teaches a developing brain that drinking is the way to “cope” with a host of teen- and life-in-general triggers, a pattern that can become a destructive coping behavior going forward.

It is estimated that 90 percent of adults who developed severe alcohol or other drug use disorders (addiction) started using before age 18 and half started using before age 15.42 And, contrary to popular belief, the Europeans do not have underage drinking (or other drug) abuse prevention under control, either.43 Check out the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs online to learn more about this fact.

Social Environment. The home, neighborhood, peer groups, and community within which a child grows and lives also influences early brain wiring. [Remember: it’s a combination of “inputs,” genetics, and brain developmental stages that wires and maps a brain. By the same token, that wired and mapped brain is interpreting everything that comes at it from that mapped brain’s perspective.] If it is stable, nurturing, and without excessive drinking, for example, a child’s brain has the opportunity to wire and map “normal” thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and model “low-risk” drinking when (or if) they decide to drink as an adults.

On the flip side, if a child/teen/young adult lives or works or goes to school in an environment where heavy drinking (or other drug use) is the norm, they will likely drink or use other drugs to that same level. Unfortunately, that same level may not work in their brains the way it works in the brains of their co-workers, family members, fellow students, or friends (and frankly it’s likely not working all that well in those other brains, either).

And lastly, if an adult is living in a social environment with heavy drinking or one wrought with stress (like living with a loved one who has an alcohol use disorder), they, too, may turn to alcohol for relief or the “thing to do” when living in that environment. Not only this, but people who abuse alcohol are fully capable of developing alcoholism as adults in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and beyond, regardless of their social environment, because of having experienced other key risk factors. This was the case for my mom.

Childhood Trauma. Childhood trauma (which can have strong connections with social environment) refers to traumatic or stressful events happening to a child before age 18. As you read in Chapter 4, childhood trauma has a profound impact on how, or if, brain cells “talk” to one another. This impact is the result of what is now understood to be toxic stress. This is the type of stress that occurs when neural networks controlling the fight-or-flight stress response are repeatedly activated. These neural networks are also in the Limbic System.

The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University explains that toxic stress “can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity – such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship – without adequate adult support.”44

Toxic stress can actually change the physical development and function of a child’s brain (also referred to as brain architecture).45 These brain changes affect how a child copes. In other words, how they express anger, fear, powerlessness; how they interpret and respond to other people’s words and actions; how or if they trust; and how they learn, as examples. These brain changes, in turn, have a profound impact on whether that child’s brain will seek drugs or alcohol for their brain- soothing qualities [chemicals working on the dopamine-reliant pleasure/reward neural networks, for example]. They will also impact how that child’s brain will interact with the chemicals in alcohol or other drugs if they do drink or use because of the brain changes caused by the toxic stress. Toxic stress and its role in all of this is more fully explained in Part 4.

And about childhood trauma... Much of what we now understand about the role childhood trauma has on the developing brain; its influence as a key risk factor for developing alcoholism (or other drug addictions); and why treating childhood trauma is key to successfully treating alcoholism is the result of the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. (ACE stands for Adverse Childhood Experiences.) This is such an important understanding that I have added a section on ACEs and the Childhood Trauma Connection.

Basic brain facts helps explain

...much of the science behind what I've described above on why substance use disorder and brain developmental stages share a mutual cause-and-effect relationship. To that end, I invite you to download Chapter 4: Basic Brain Facts -- an excerpt from my latest book, 10th Anniversary Edition If You Loved Me, You'd Stop.

Comments (4)