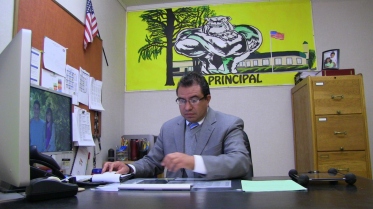

Instead of suspending or expelling the six-year-olds, as happens in many schools, Principal Godwin Higa ushers them to his side of the desk. He sits down so that he can talk with them eye-to-eye and quietly asks: "What happened?" He points to one of the boys. "You go first."

In this school, a fight turns into a teachable moment on how to resolve conflict. Higa walks them through the process:

Establish what happened. "He grabbed my shirt," says Boy No. 1. "He pushed me down," says Boy No. 2. They fidget. Their faces pinched into frowns, they can barely look at each other.

Have them accept responsibility. "Did you grab his shirt?" Higa asks Boy No. 2. Higa's tone is quiet, conversational, his demeanor non-threatening. "Did you push him down?" he asks Boy No. 1. It takes a few back-and-forths before the boys nod, eyes downcast.

Have them tell each other how they felt about having their shirt grabbed and being pushed down. Neither boy liked it. They acknowledge that they could have seriously hurt each other.

Have them apologize and agree that they won't do it again. Both boys nod, curl their fingers in front of their mouths and murmur into their fists, "I'm sorry". They don't really mean it. And they still can't look at each other. Heads hanging, they think this is over and slowly turn to leave.

Higa keeps talking. "What if it happens again? What will you do?" The boys stop, turn and stare wide-eyed at him. They don't expect these questions. "You have to solve this," says Higa. "You can talk to each other, help each other." They look at each other in a slight panic as performance anxiety replaces their discomfort with each other. They think, confer, and then tell Higa that each would ask the other not to continue. Or they would ask a teacher for help.

"Congratulations!" smiles Higa. "You figured this out." The boys beam with unexpected pride.

"And what do you do when you've worked something out?" They look at him for guidance. "You shake hands!" They grin and shake hands. "Can you give each other a hug?"

They wrap their arms around each other and squeeze tight. Higa laughs and sends them to lunch.

Fifteen minutes later, they knock on his door and peek in, all smiles. "Mr. Higa, we're friends now," chirps Boy No. 2.

"Yes," says Boy No. 1. "He asked me to be his friend and I said, 'Yes!'"

They grip each other in another hug to demonstrate and run off to their classroom. Instead of returning to class with brains clogged with anger and revenge, they're happy, open and ready to learn.

Higa chuckles as he watches them go. "The fifth-graders only shake hands," he muses. "They don't like to hug."

___________________________________

If fixing school discipline were a political campaign, the slogan would be "It's the Adults, Stupid!"

A sea change is coursing slowly but resolutely through this nation's K-12 education system. More than 23,000 schools out of 132,000 nationwide have or are discarding a highly punitive approach to school discipline in favor of supportive, compassionate, and solution-oriented methods. Those that take the slow-but-steady road can see a 20% to 40% drop in suspensions in their first year of transformation. A few -- where the principal, all teachers and staff embrace an immediate overhaul -- experience higher rates, as much as an 85% drop in suspensions and a 40% drop in expulsions. Bullying, truancy, and tardiness are waning. Graduation rates, test scores and grades are trending up.

The formula is simple, really: Instead of waiting for kids to behave badly and then punishing them, schools are creating environments in which kids can succeed. "We have to be much more thoughtful about how we teach our kids to behave, and how our staff behaves in those environments that we create," says Mike Hanson, superintendent of Fresno (CA) Unified School District, which began a district-wide overhaul of all of its 92 schools in 2008.

This isn't a single program or a short-term trend or a five-year plan that will disappear as soon as the funding runs out. Where it's taken hold, it's a don't-look-back, got-the-bit-in-the-teeth, I-can't-belieeeeeve-we-used-to-do-it-the-old-way type of shift.

The secret to success doesn't involve the kids so much as it does the adults: Focus on altering the behavior of teachers and administrators, and, almost like magic, the kids stop fighting and acting out in class. They're more interested in school, they're happier and feel safer.

"We're changing the behavior of the adults on campuses, changing how they respond to poor behavior on kids' part," says Mary Ann Carousso, head of student services for Kings Canyon Unified School District in Central California, which launched a five-year plan in 2010 to revamp the district's 20 schools.

This movement began about a dozen years ago, and has gained momentum in the last five years. The first schools to yank themselves free of the knee-jerk punitive response to bad behavior did so based on two unrelated developments.

First, suspensions and expulsions soared to ridiculous levels. By 2007, a stunning one-quarter of all public high school students had been suspended at least once during their school careers, according to a National Center for Education Statistics 2011 report. The numbers were worse for boys of color. One-third of Hispanic boys and 57% of black boys had been kicked out of school at least once.

Further, the report noted that more than three million kids are suspended or expelled each year -- in 2006 that number was 3,430,830. In California, 464,050 children were kicked out of school that year, many more than once, for a total of more than 800,000 suspensions and expulsions.

The acceleration began with the adoption of broad zero-tolerance policies that spread like a prairie fire across the United States in 1995, just one year after the U.S. Congress passed the Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994. Once "zero tolerance" was locked in, teachers and principals warped it, some say, by the pressure to perform well on tests. Kick the troublemakers out, and there's less disruption and interruption in class. With those underperforming kids gone, test scores look better.

Here's the absurd part: Only five percent of these suspensions or expulsions were for weapons or drugs. The other 95 percent? "Disruptive behavior" and "other". This includes cell phone use, violation of dress code, talking back to a teacher, bringing scissors to class for an art project, giving Midol to a classmate, and, in at least one case, farting.

But punishment doesn't change behavior; it just drops hundreds of thousands of flailing kids into a school to prison pipeline. The ka-ching to us taxpayers is $292,000 per dropout over his or her lifetime due to costs for more police, courts, and prisons, plus loss of income and taxes into our civic treasuries.

"Suspensions and expulsions don't work," says Javier Martinez, principal of Le Grand High School, Le Grand, CA. His approach is: "How do I help student overcome a problem so that it doesn't happen again?"

Comments (0)