The Children’s Clinic, tucked in a busy office park five miles outside downtown Portland, OR, and bustling with noisy babies, boisterous kids and energetic pediatricians, seems ordinary enough. But, for the last two years, a quiet revolution has been brewing in its exam rooms: When parents bring their four-month-old babies in for well-baby checkups, they talk about their own childhood trauma with their kid’s pediatrician.

Wait. What’s Mom or Dad’s childhood got to do with the health of their baby? And aren’t pediatricians supposed to take care of kids? Not kids’ parents?

It turns out that just 14 questions about the childhood experiences of parents provide information critical to the future health of their baby, say Children’s Clinic pediatricians Teri Pettersen and RJ Gillespie. The answer to the questions can help determine not only if the child will succeed in school, but when the child becomes an adult, whether she or he is likely to suffer chronic disease, mental illness, become violent or a victim of violence.

They explain how this is possible.

It’s an understatement to say that raising a kid is a challenge, and not for the faint of heart. The many stressful moments of an infant or a toddler’s life include tantrums, colic, toilet training, sleep problems, colds, hitting and biting, say Pettersen and Gillespie.

“At some point, a toddler is likely to hit or bite Mom and Dad,” says Pettersen. “How will they respond?”

If parents have grown up with a lot of adversity in their lives and little help in understanding how that adversity affects their behavior and how they react to stress, they’re more likely to pass that on to their children, even if they don’t intend to, by reacting without thinking in typical “fight, flight or fright (freeze)” mode. They may hit the child, walk away from the child who’s asking for attention (albeit in a negative way), or freeze, only to be bitten or hit some more. None of that helps grow a healthy child or a healthy relationship between the parent and child.

Long story short: The physicians at the Children’s Clinic believe that asking parents about their own childhood adversity is a good start to preventing their children from experiencing childhood trauma.

Asking parents questions about their childhood trauma has made such an impact in the Portland pediatric community that, just last month, Metropolitan Pediatrics with its 30 doctors began screening the parents of four-month-old babies for the parents’ adverse childhood experiences.

Why asking parents about their childhood is a big deal

To understand why this is such a big deal, you have to go back a ways, to the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study). The ACE Study began in 1995 with 17,000 Kaiser Permanente members who volunteered to participate in research on the long-term effects of childhood adversity. The study measured 10 types of childhood adversity: sexual, physical and verbal abuse, and physical and emotional neglect; and five types of family dysfunction – witnessing a mother being abused, living with a household member who’s an alcoholic or drug user, who’s been imprisoned, or diagnosed with mental illness, or loss of a parent through separation or divorce.

The study revealed the remarkable prevalence of ACEs — 64 percent of study participants had at least one — and how childhood adversity leads to the adult onset of chronic disease, mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence.

It also showed that the more types of childhood adversity a person has, the more likely that person will suffer health problems. Compared with people who have zero ACEs, people with an ACE score of 4 are twice as likely to be smokers, 12 times more likely to attempt suicide, seven times more likely to be alcoholic, and 10 times more likely to inject street drugs. Compared to people with zero ACEs, people with an ACE score of 6 are more likely to have a shorter lifespan – by 20 years.

Research explains the link by showing how the toxic stress of trauma harms the structure and function of children’s developing brains, how it embeds in our bodies, and how parents can pass it on to children. Ongoing research is demonstrating that building resilience can help people heal, and that systems can stop traumatizing already traumatized people.

The two principle investigators of the ACE Study — Dr. Robert Anda and Dr. Vincent Felitti — thought that as soon as the medical world learned about this new knowledge with the publication of the first of 70 papers in 1998, physicians would clamor to be the first to integrate ACEs into their practices.

After all, says Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician who began screening kids for ACEs in 2009 at the BayView Child Health Center in San Francisco, just as pediatricians ask parents if there’s lead paint in their home because they know that exposure to lead can harm children, so they should ask about a kid’s exposure to ACEs. That’s because a high ACE score increases the likelihood that the child will grow up to suffer from heart disease, cancer, autoimmune diseases, depression, suicide, and/or a multitude of other problems.

But Anda and Felitti’s assumptions about the medical community were dead wrong. The number of U.S. pediatricians who have integrated ACEs into their practice is fewer than one percent. The percentage of other types of primary care physicians who are asking about ACEs is even less.

Due to the efforts of Dr. Robert Block, outgoing president of the American Academy of Pediatrics — and current president Dr. Sandra Hassink, who’s carrying on with the message — most pediatricians know about the ACE Study. So why don’t they use it?

Ask 1,000 physicians, and you’ll get these same five responses: “There’s no time.” “It would just open a Pandora’s Box”…or “a can of worms.” “I don’t know what to say.” “We don’t have the resources (such as counselors).” “Asking the questions might make the patient have a full mental collapse.”

Doubts and fears in the pediatric clinic

And that’s exactly what the Children’s Clinic pediatricians told Pettersen and Gillespie. In 2013, the two started a pilot project with six of their partners. It went so well that the entire clinic decided to integrate ACEs, even though the other 19 pediatricians expressed their doubts and fears.

Two years in — with more than 1500 parents having taken the survey — “the 27 pediatricians who are using the survey say they’d never go back to the way they did things before,” says Gillespie.

Except for two who weren’t confident about how to have a conversation about ACEs, all of the pediatricians said that none of their fears materialized. Not a single parents broke down. The average time spent on the topic was three to five minutes. And all pediatricians said that it wasn’t as scary as they anticipated.

Most parents love the questionnaire, says Gillespie. The responses include: “I think this questionnaire is an excellent idea.” “Thank you for letting us participate in this.” “I feel confident I’m going to be a great mom.” Only one said, “This is weird.”

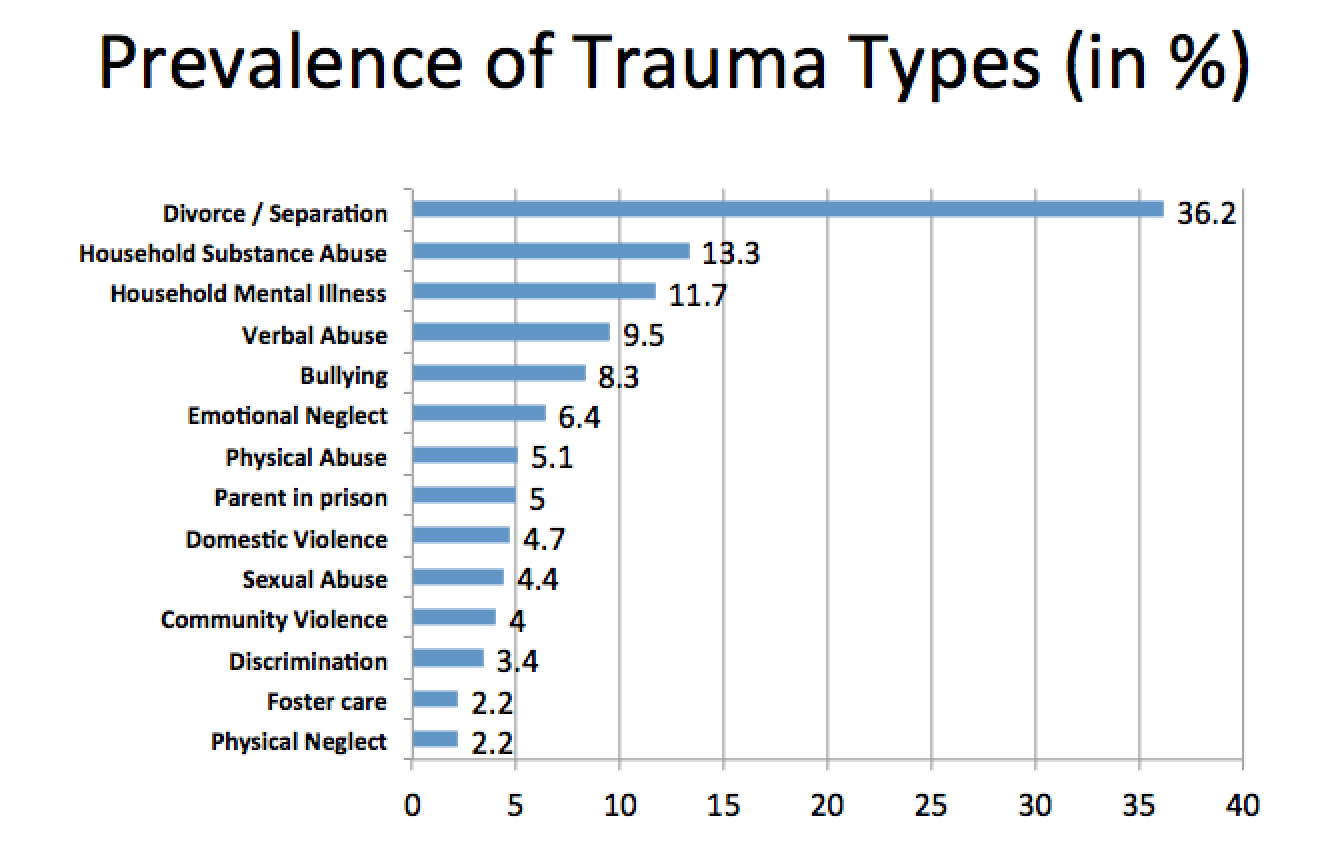

This is how the screening works, says Pettersen: The parents fill out the questionnaire in the waiting room. The pediatricians decided to add four questions to the 10-question ACE survey: bullying, discrimination, community violence and foster care. They also include a resilience questionnaire to point out resources and strengths the parents had or have, so that they can build on them, and to see if people with high ACE scores and high resilience scores have fewer challenges than people with high ACE scores and low resilience scores.

“Regardless of ACE scores and resilience scores,” says Pettersen, “we want this to be a strengths-based approach for all families.”

The pediatrician the parents are visiting quickly reviews the results. On meeting with the parents, says something like the following, depending on their ACE scores:

- “It looks as if you had pretty supportive family. Growing up experiencing good role models can make parenting much easier than if you didn’t have that experience. You’ll still have challenges, because none of us is perfect, and that is OK. Parenting and discipline is something we will talk about regularly as your child grows up.”

- “Thank you for completing the questionnaire today about your childhood. We know it can be difficult for some people to do. It looks as if you had some very difficult experiences during your childhood. Most parents I talk to with similar experiences feel they have worked through some of these experiences but still get tripped up by others. I’m wondering if that is the case for you? How do you think these experiences affect your parenting today?”

The responses, says Pettersen, have ranged from, “This one’s kind of hard for me still,” or “I’ve gone back into counseling for this one”, or “I plan to go back into counseling.”

When asked what kinds of support they needed, most parents said parenting classes, support groups, or more information on the web.

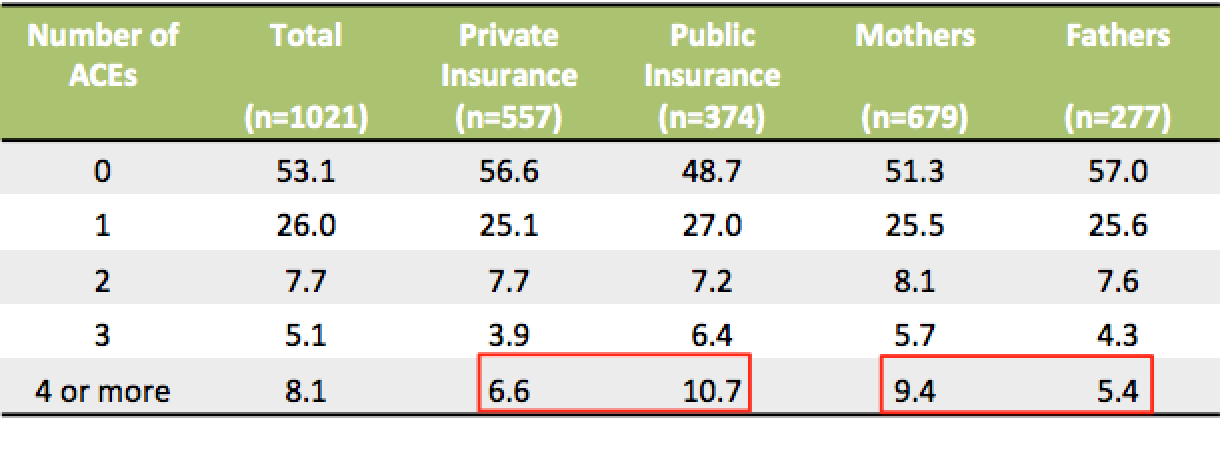

Of the 1,021 parents whose surveys have been analyzed, 53 percent had an ACE score of zero, and a resilience score of 56 (out of 60), while 8 percent had an ACE score of four or more, with an average resilience score of 48. Of those with private insurance, 6.6 percent had ACE scores of 4 or higher; of those with public insurance, 10.7 percent had ACE scores of 4 or higher. And, remarkably, nearly twice as many women as men had ACE scores of 4 or higher.

Although this shows that more people with lower incomes have ACEs, childhood adversity is reflected in all income groups.

Although this shows that more people with lower incomes have ACEs, childhood adversity is reflected in all income groups.

Of the 650 surveys that had the extra four questions, and there were 116 “yes” answers. Eleven of those moved parents’ total ACEs from below to greater than 4, 40 parents saw their score move from zero to 3. The rest added on to an already high ACE score.

Gillespie analyzed the ACEs of the clinic’s Spanish-speaking population, and found that 8.6% of the parents had an ACE score of 4 or higher, not much different than the English-speaking population (8.1%). And although the #1 and #2 ACEs were the same — divorce/separation and parental substance abuse — the third and fourth most common ACEs for the Spanish-speakers were emotional neglect and discrimination.

The 19 pediatricians whom Gillespie surveyed said a few things surprised them: parents’ willingness to talk about their ACES, the resilience of the parents who’d suffered severe abuse, how grateful the parents were at being asked the questions, the sense of relief they expressed at no longer having to keep their experiences a secret, and how easy it was to have conversations with parents about their ACEs.

That shows that “listening is therapeutic,” says Gillespie. “Our key message to parents is that ‘You’re not alone; it’s not your fault; and I will help you.”

Does asking parents about ACEs improve the health of their babies?

The most important question, of course, is: Has asking these questions…does having this conversation…make a difference in children’s health?

It’s too soon to have any quantifiable data, but all the pediatricians have been able to offer parents guidance and resources that the parents would not have received if the ACE questions had not been asked.

Take the example of a mother who revealed that when she was two years old, she’d been abandoned by her mother. When Gillespie said it was okay to let her baby cry a little when he was learning to go to sleep by himself, that “triggered a lot of fear,” he says.

“She couldn’t and didn’t do it with her first child,” he explains. “We’d talked about sleep problems many, many times, and I never got to why she wasn’t following my advice until she filled out the ACE survey. Once she said the words about her fears out loud, she immediately felt different about sleep training.”

One parent told the pediatricians about a mentally ill, suicidal brother that was living with the family. Another said she was depressed, on medication and seeing a counselor. Several expressed worry about how a divorce was affecting their children. A parent with an ACE score of 5 grew up in a toxic household where verbal abuse and yelling were common. In these situations, parents may not be aware of how their experiences affect their parenting or work-life balance, says Gillespie. The pediatricians can provide anticipatory guidance, such as helping the mom with the ACE score of 5 talk through her reaction to a “yelling” infant, and point her to some parenting resources.

By knowing that parents have experienced trauma, pediatricians can help them develop skills and ideas for taking care of themselves, to encourage them to ask for help, to give them resources so they can learn what healthy parenting looks like, including learning how to play with their child and using discipline that’s appropriate for the child’s age, and to help them improve their child’s social and emotional environment.

Eventually, say Pettersen and Gillespie, all pediatricians will be integrating ACEs into their practice, because it’s crucial to making sure that kids have a healthy childhood — which helps them avoid chronic disease and mental illness when they’re adults.

So far, there isn’t an AAP-certified screening tool for ACEs. However, the science is so compelling that it gives clinics the freedom to try different approaches in different clinic settings before one is developed, says Pettersen, which may help in developing the tool, “because different clinic settings are different.” Even though most families have ACEs, suburban Portland is different than South Los Angeles, CA, which is different than Beverly Hills, CA, and the Bronx, NY.

Next steps

The pediatricians want to expand ACEs screening to parents of older children, as well as figure out how to use it with their adolescent patients. The Children’s Clinic staff itself has started learning about ACEs and trauma-informed practices.

“Nurses have said that now they understand their lives better,” says Pettersen. “And it helps them put into context “difficult” parents. Those whom they have referred to as “noncompliant”, they can think about through a different frame, one that’s less pejorative and more understanding.”

The clinic staff is also starting to examine its own work policies through a trauma-informed lens, and is identifying what’s trauma-informed and what’s not to make the clinic a more resilient workplace.

Gillespie continues gathering data on the revolution at the Children’s Clinic, and, with the support of Healthshare, is working with the Oregon Health Authority and the Transformation Center to refine the project to prepare to spread it to other practices.

Last year, Pettersen retired from Children’s Clinic, and is now working with the Oregon Pediatric Society to provide trainings about ACEs and trauma-informed care to clinicians throughout Oregon.

“My focus is on education,” she says, “starting with primary care. There are still many physicians who have never heard of the ACE Study. In primary care, we like to think we are all about prevention. This is prevention with a capital P. We’d like to see if we can bring what we have learned and experienced at the Children’s Clinic to scale.”

It’s also important for other sectors in the community — education, juvenile justice, criminal justice, social services, the faith-based and business communities — to become educated about ACEs and begin to integrate trauma-informed, resilience-building practices, too, she says.

“It isn’t all on our shoulders,” she says. “The stronger and healthier communities are, the better off kids will be in those communities.”

Comments (1)