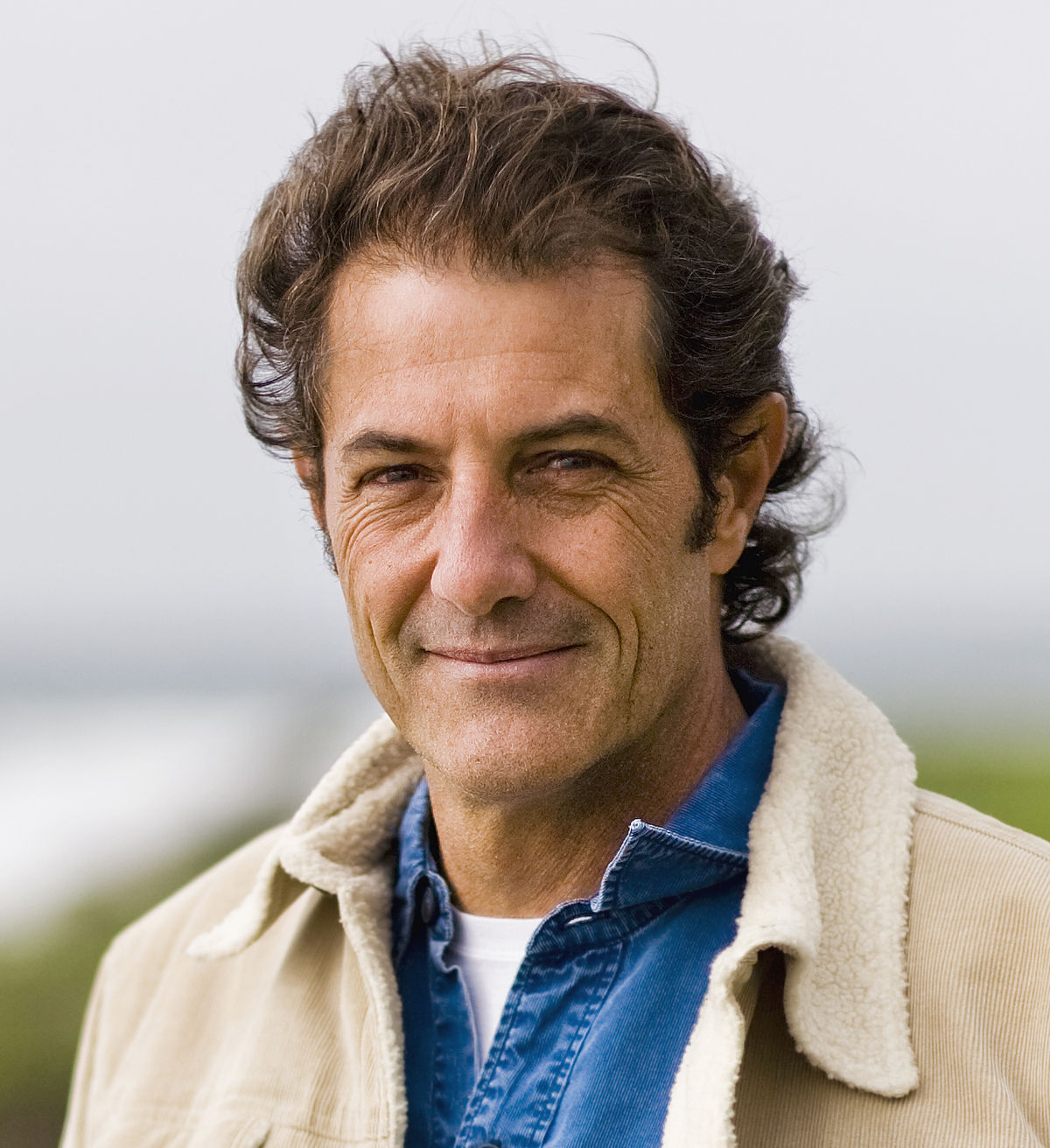

One of the five domains of post-traumatic growth is spirituality. Helping us understand the role of spirituality in recovering from trauma at the Echo Frontiers of Resilience conference is Shaun Tomson. If you think the name and face look familiar then perhaps you know him from his days as a world champion surfer. Shaun needed every single one of the lessons he had learned about facing challenges in the form of towering waves and overcoming wipe-outs when he lost his 15-year-old son to a tragic accident. How do you get over the death of a child? In many ways, it is the ultimate challenge, the ultimate loss.

One of the five domains of post-traumatic growth is spirituality. Helping us understand the role of spirituality in recovering from trauma at the Echo Frontiers of Resilience conference is Shaun Tomson. If you think the name and face look familiar then perhaps you know him from his days as a world champion surfer. Shaun needed every single one of the lessons he had learned about facing challenges in the form of towering waves and overcoming wipe-outs when he lost his 15-year-old son to a tragic accident. How do you get over the death of a child? In many ways, it is the ultimate challenge, the ultimate loss.As Judith Herman says in her book Trauma and Recovery that “people spontaneously seek their first source of comfort and protection. Wounded soldiers and raped women cry for their mothers, or for God. When this cry is not answered, the sense of basic trust is shattered. Traumatized people feel utterly abandoned, utterly alone, cast out of the human and divine systems of care and protection that sustain life.”

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel cried out to God at Auschwitz. “Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever. Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.”

And yet, if Echo’s trainings are anything to go by, when we ask participants to identify an area where they have experienced post-traumatic growth, spirituality is the domain most frequently chosen and inspires the most passion. How do we professionals reconcile that with our (mostly) secular service provision and our own loss or absence of faith?

Dusty Miller (author of “Women Who Hurt Themselves”) a therapist and incest survivor talks about her unease at the “spiritual thinness” of the therapeutic work she had been doing.

In 1995, I drove to Burlington, Vermont, for a weekend workshop... Led by a white man, a Maori man, and a Samoan woman, all from New Zealand, the group opened every session with chanting and prayer, challenging us bemused, secular Americans to do the same.

That day, I awoke to the spiritual thinness of the therapeutic work we were doing…

I thought variously of Gandhi's independence movement, of Alcoholics Anonymous, and of the Civil Rights movement, all of which had flourished rather than imploded. What had been their secret? Despite their enormous differences, all had transformed participants – and the culture at large – in a way I can only describe as spiritual. All had acted in the present moment – cognizant of, but not enslaved by, the past. All had faith in something bigger than themselves, and none demonized their purported enemies. Could the trauma survivors' movement do the same?

If you are intrigued by this discussion, please come to Shaun’s workshops where he will talk about his own walk of faith and 'the surfer’s code' that has given him purpose and meaning in his life as he helps others cope with traumatic loss.

And just as a reminder to ‘never say never,’ toward the end of his life, Elie Wiesel reconciled with his God:

“Master of the Universe, let us make up. It is time. How long can we go on being angry? ...I now realize I never lost [my faith], not even over there, during the darkest hours of my life... But my faith was no longer pure. How could it be? It was filled with anguish rather than fervor, with perplexity more than piety... What hurt me more: your absence or your silence?

In my testimony I have written harsh words, burning words about your role in our tragedy. I would not repeat them today. But I felt them then. I felt them in every cell of my being… In my childhood I did not expect much from human beings. But I expected everything from you.

Where were you, God of kindness, in Auschwitz? What was going on in heaven, at the celestial tribunal, while your children were marked for humiliation, isolation and death only because they were Jewish?

These questions have been haunting me for more than five decades...

At one point, I began wondering whether I was not unfair with you. After all, Auschwitz was not something that came down ready-made from heaven… Let us make up, Master of the Universe. In spite of everything that happened? Yes, in spite. Let us make up: for the child in me, it is unbearable to be divorced from you so long.”

Comments (0)