For the leaders of Sarasota Strong (or "SRQ Strong") Florida, anti-racism work isn’t about inviting people of color to tables long-occupied by white professionals fluent in academic jargon and theories of change.

It’s about venturing, with humility and openness, into spaces where Black people worship, work and live.

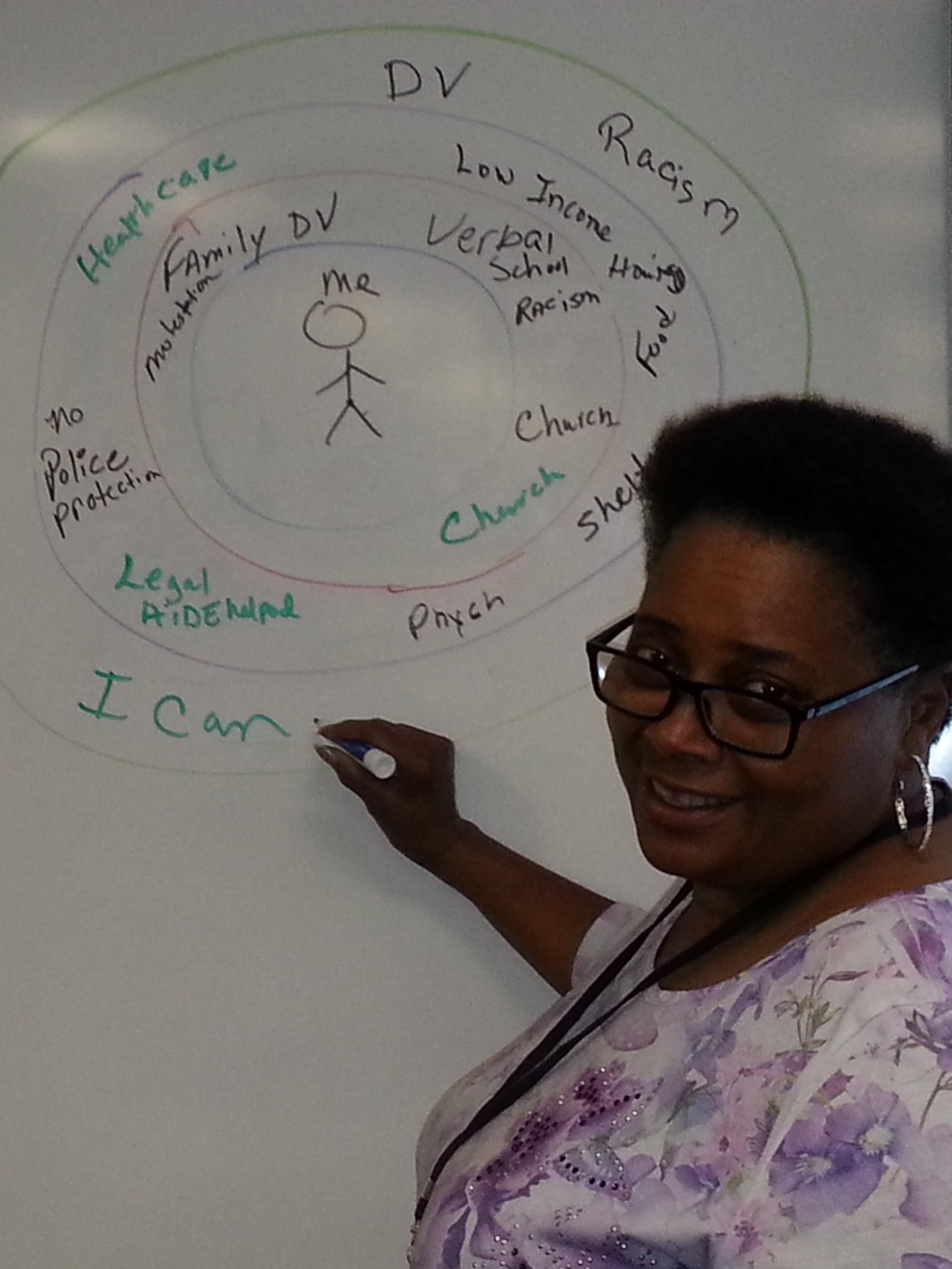

Which is why, before SRQ Strong even had a name or held a formal event, educator/minister Helen Neal-Ali launched an eight-session series of healing workshops at Community Bible Church, a building painted white and purple and surrounded by a chain-link fence in Newtown, a majority-Black southwestern Florida neighborhood in which nearly 40% of residents live below the poverty level.

At first, the response was wary. But by the fourth session, after discussions of racism, trauma triggers and self-image, Neal-Ali says, she could feel a shift. When the series ended, workshop participants created a play about trauma and healing and performed it for the congregation.

Equally important, Neal-Ali’s workshops opened a door to trust and conversation: about shared values and disparate experiences, about how people learn bias and about the historically-unspoken trauma of racism in America. “I think we’ve really broken down a wall,” says Neal-Ali. “People in Newtown feel like we’re here to help, not to take from their community.”

For SRQ Strong, a grassroots, collective effort that formed 18 months ago with the vision of creating “a community that cares for itself,” anti-racism work was always at the core, says co-founder Andrea Blanch, director of the Center for Religious Tolerance.

“We explicitly said, ‘Okay, we don’t even have a right to claim we are working toward becoming trauma-informed if we are not willing to confront racism directly.’ We recognized that racism is one of the largest contributors to trauma in our society, if not the largest.”

That’s one of the reasons why the group chose Father Paul Abernathy’s Pittsburgh-based model of trauma-informed community development, the Neighborhood Resilience Project—which trains organizers to help community members identify local problems and create strategies to solve them—as its organizing framework. It’s why SRQ Strong joined the local anti-racism coalition and helped draft that group’s recent newspaper ad condemning racism, supporting protest and demanding police accountability.

And it’s the reason why the network’s first community forums (held in person before COVID-19) featured a formerly incarcerated Black woman who talked about growing up in public housing and another Black woman who spoke of her experience with domestic violence in the church.

Anti-racist work, especially for white people of privilege, means doing more listening than talking, Blanch says. “Black, indigenous people and people of color understand trauma and resilience; they know it in their bones, in their history, and if we want to be any help at all, we need to acknowledge and amplify their experience.”

At the 2017 Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) National Summit in Philadelphia, Kanwarpal Dhaliwal, co-founder of Richmond, California’s RYSE Center, a social justice, education and healing space for youth, challenged attendees to think beyond family-based ACEs to systemic harms: historical trauma, structural racism, capitalism and colonialism. “If it’s not racially just, it can’t be trauma-informed,” she said.

For networks around the country that share the goal of preventing childhood adversity and building resilience, that declaration has taken on new urgency.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shed a devastating light on race-based health disparities in the United States, followed by the recent police killings of Black women and men and protests that convulsed the nation, some networks have drafted statements calling for alternatives to policing and affirming their commitment to Black Lives Matter.

Others have vowed to frankly examine racism from within: recruiting more leaders who are people of color, adding more inclusive language and diverse images to their websites and emphasizing their commitments to racial equity.

The Trauma Matters Delaware steering committee recently issued a statement noting that “long standing systemic oppression and structural violence” has traumatized African-Americans and communities of color. In Walla Walla, Washington, the Community Resilience Initiative’s fifth annual Beyond Paper Tigers conference (held virtually June 24-25, 2020) focused on diversity, equity and inclusion; the conference description notes that “systemic racism is a public health crisis” and one of the keynote speakers, former W.K. Kellogg Foundation Vice President Dr. Gail C. Christopher, spoke on “Racial Healing.”

Alive and Well Communities, a regional network in Kansas City and St. Louis, drafted a call to action, featured on its website, that demands leaders “continue seeing, naming and disrupting racial inequity.”

In practice, says Alive and Well president Jennifer Brinkmann, that means fostering specific, honest conversations about racism—a priority for the network long before COVID-19 and recent instances of police brutality—rather than couching the issue in the more vague language of “health disparities” or avoiding it entirely. “So often, we think we can fix racism by not talking about it directly, just by being good people or applying some other theory of change,” she says.

Combating racism, Brinkmann says, involves “getting out of the way and creating opportunities for community members to own the work. And then it means using our collective power and privilege to advocate for change that specifically benefits the Black community and others who experience oppression.”

To further that goal, Alive and Well hires community consultants—“natural neighborhood leaders,” Brinkmann says—who receive training on trauma and toxic stress, then help their neighbors identify issues, such as an excess of vacant housing, that they can address together.

Alive and Well’s “impact series,” held in Kansas City libraries, has focused on topics that intersect with racism, such as discussions of homelessness or Black women’s experiences with health care.

Some ATR network leaders note that the trauma-informed movement itself can sometimes adopt a “white savior” approach, using language and approaches that stigmatize, re-traumatize and ignore the centuries-old healing practices, resilience and wisdom of indigenous, tribal and people-of-color communities.

“People come in and want to introduce mindfulness or yoga, as if we have no healing traditions ourselves,” says Father Abernathy, who transformed a faith-based ministry into Pittsburgh’s Neighborhood Resilience Project, which emphasizes inclusion and collective problem-solving at the micro-community level—15 to 36 households in a given area. “It’s time that we honor and raise up experts who are often experts as a result of their experience of trauma.

“There has to be a different distribution of power,” Abernathy says. “Agencies and institutions are trying to get African-Americans to sit down at their tables. Many people don’t go, and many don’t stay. We have to get to the question: How can we be invited and included in their table?”

When Teena Brooks joined the board of the Campaign for Trauma-Informed Policy and Practice (CTIPP), a national, volunteer-led effort to embed trauma-informed approaches into national policy, she noticed the absence of explicit anti-racist language on the campaign’s website and materials.

She joined CTIPP’s anti-racism working group to help address that gap. “There was a feeling that anti-racism practices weren’t embedded in the work we were doing,” says Brooks, who works as a health administrator with a focus on community engagement. “We began looking at our messaging, doing a scan of our website: Do the images represent inclusion?”

Along with CTIPP staff, members of the anti-racism working group developed a statement in response to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent national reckoning about race, violence and police power, including the vow to “listen to those impacted by racism and examine our own biases.”

Even the language of ACEs and resilience can be blinkered where race is concerned, Brooks says; she worries about stamping communities of color as “traumatized” and failing to see beyond that label.

“It’s easier to talk about what’s wrong with communities, how they’re broken and how that’s somehow their fault,” she says. “That takes us away from our commitment to looking at structural racism.”

Examining racism among CTIPP board and staff has been “hard,” Brooks says. “But I think we’ve had great conversations. It’s definitely work that I think will be unfolding. For me, any organization that says it’s trauma-informed has to be anti-racist.”

Anndee Hochman is a journalist and author whose work appears regularly in The Philadelphia Inquirer, Broad Street Review and in other print and online venues. She teaches poetry and creative non-fiction in schools, senior centers, detention facilities and at writers' conferences.

This article originally appeared on Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) on July 1, 2020. MARC provides tools and inspiration—by networks, for networks—using the science of ACEs to build a just, healthy and resilient world. Visit MARC.HealthFederation.org for more.

Comments (0)